Well, if you say so…

Crabtree Falls, VA

Located in the George Washington National Forest, these are the tallest set of waterfalls east of the Mississippi River. At an elevation of 1,670′, with a height frequently listed as 1,214′ (topographical maps show the height as closer to 1,000′), there are five drops. Thought to have been named for settler William Crabtree, who settled…

Trip To Virginia

Normally, by this time of year, we would have been to at least one destination. 2020 has certainly proven itself a very different sort of year thus far. Later this week, we’ll be taking a journey by car to rural central western Virginia. We have very high hopes for this adventure (in great part due…

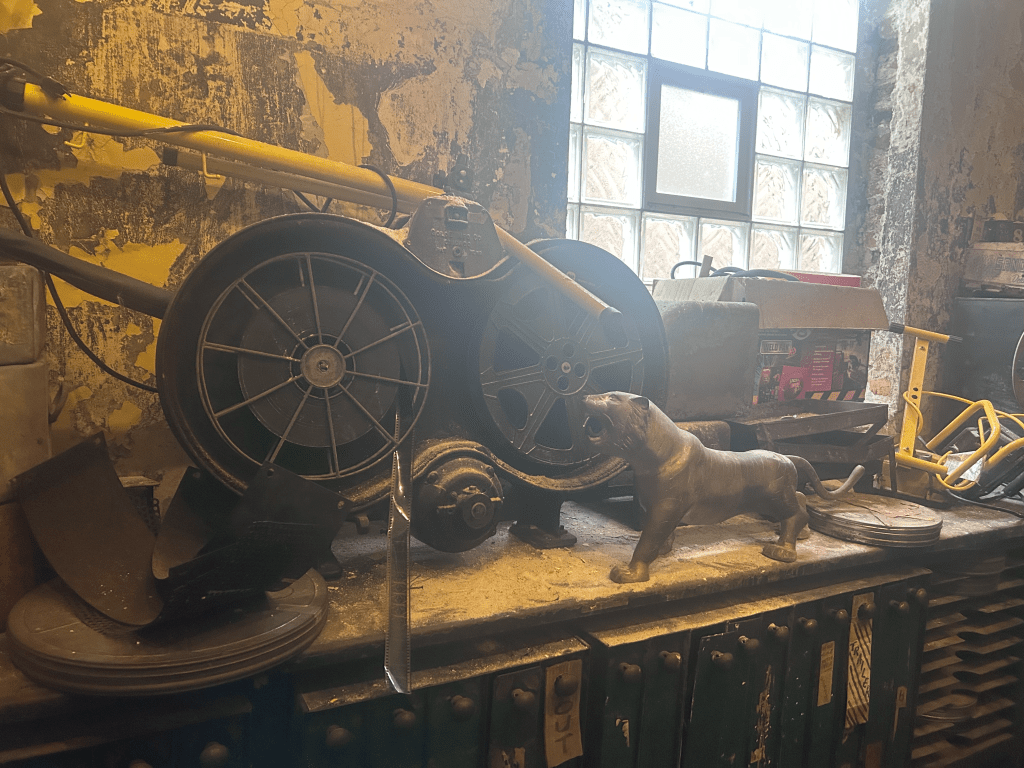

Apollo’s 2000 Theatre Chicago, IL

Having missed the CAC’s (Chicago Architecture Center) Open House (last year, I was intent on visiting several sites this year. Amongst these was Apollo’s 2000 Theatre in Little Village. The building is currently functioning as a prominent performance and event venue, situated within a historic theater originally constructed in 1917 as the Marshall Square Theatre. This edifice was conceived to exhibit the then-nascent entertainment of silent motion pictures. Characteristic of most early twentieth-century cinemas, the Marshall Square Theatre featured striking architectural design, specifically a Beaux Arts exterior and interior, complemented by elaborate lighting, all intended to captivate patrons and evoke an ambiance of opulence and fantasy. The theater’s commission originated from brothers Louis and Meyer Marks, notable Chicago film exhibitors who, in the subsequent decade of the 1920s, would proceed to erect some of Chicago’s most lavish movie palaces. Alexander L. Levy, the Marks’s preferred architect and a burgeoning master of cinematic theater design, was responsible for the Marshall Square’s architectural conception.

In the spring of 1917, the Chicago Tribune reported that theater operators and brothers Louis and Meyer Marks, had partnered with Julius Goodman and Louis Harrison to build a theater at the southeast corner of W. 22nd Street (W. 22nd Street was later renamed W. Cermak Road, after the Mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermak, who died from a bullet in Miami meant for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt) and S. Marshall Boulevard. The new theater was named after Marshall Square, the historic name for the surrounding neighborhood that has since been replaced by the more widely-recognized term Little Village. The announcement for the new building identified Alexander L. Levy as the architect and detailed plans for 2,600 seats in the theater as well as rental storefronts and offices. Some aspects of the planned building never materialized, such as Turkish and steam baths, and the seating capacity was scaled back to 1,800. After eight months of construction, the theater opened on December 22, 1917, with a screening of “His Mother’s Boy” and the “The International Sneak,” two silent films accompanied by a ten-piece orchestra, organ, and vocalist Ruth Holdt. The architectural focal point of the building is the theater entrance which is treated as a tall arch framed by square towers. The top of the arch terminates with a cornice, and the flanking towers

are topped with domes, all rendered in terra-cotta with classical details. A secondary terra-cotta arch frames a flat panel of terra cotta with ornamental terra cotta including sculptured eagles and a mascaron, or female face. A large, illuminated blade sign projecting from the arch identifies the building as Apollo’s 2000. Below this, a marquee projects from the façade over the sidewalk-level ticket booth and the theater’s eight entrance doors. Like many theaters in Chicago of this vintage, the current blade sign and marquee are not original. The original blade sign, reading “Marshall Square Theatre” was significantly lower in height. The original marquee was thinner than today’s version and was decorated with classical detail to compliment the design of the building.

To the left of the theater entrance, a row of six storefronts marches eastward on Cermak Road. The stores have large storefront windows with transoms and recessed entrances with mosaic tile thresholds. A terra-cotta-framed entrance marked “Offices” in the middle of the storefront row leads to rental offices on the second floor above the storefronts. The second-floor office windows are set in terra-cotta arches with classical molding and cartouches. This storefront and office wing is topped with a prominent terra-cotta cornice with shields and classical festoons.

Historic photos of the building show that the cornice was originally topped with terra-cotta finials with incandescent bulbs, though these were removed early in the building’s life. Most of the remaining exterior light sockets encrusting the terra cotta remain and number in their hundreds, if not thousands, creating a spectacular level of architectural illumination by 1917 standards.

Like the exterior, Beaux-Arts ornament is generously employed on the interior of the theater. Entrance to the theater is made through a grand lobby, a 30-foot square in plan and one-story in height. The ceiling and wall surfaces are heavily ornamented with classical details, moldings, cornices and panels, all with a gold painted finish. The lobby walls have built-in picture frames designed for the display of movie posters. Recessed cove lighting and a suspended chandelier provide illumination. Passing through this lobby, one enters the theater auditorium which measures 130 feet from stage to rear and 80 feet wide. The stage and proscenium vie with a heavily ornamented ceiling

for visual superiority. The stage and proscenium are framed with full-height fluted, Corinthian columns carrying an entablature spanning the stage. The main volume of the ceiling is a flat rotunda framed with an ornamental band of cartouches, scallop shells and modillions. Chandeliers hang from molded starburst patterns in the ceiling. The walls of the auditorium are relieved with panel molding. The projecting booth at the rear of the auditorium is carried on scagliola columns with the appearance of buff marble.

A little over a decade after the Marshall Square Theatre opened, it made the transition from silent films to “talking pictures.” However, musical programs remained an attraction at Marshall Square Theatre well into the 1920s when Louis “Doc” Webb led popular organ solos accompanied by slides projected onto the screen. A motion picture trade magazine known as the Exhibitor’s Herald World noted that in 1929 “a two-reel all-talking picture was booed, and patrons refused to listen to it. But silence took place when ‘Doc’ started his solo. This house is a cozy little theatre and has big pulling power at the Box Office, and ‘Doc,’ we believe, helps in that direction quite a bit too.” Around the same time, the Marks Brothers, the original owners of the theater, sold the building to Paramount Publix Corporation (later Paramount Pictures) which hired the Chicago firm of Balaban and Katz to manage the Marshall Square. In 1936, architect Roy B. Blass remodeled the Marshall Square Theatre, adding air conditioning and a larger blade sign that exists today though refaced with the building’s current name.

Architect Alexander L. Levy (1872-1955)

The Marshall Square Theatre, now Apollo’s 2000, was designed by architect Alexander L. Levy. He was born to Jewish immigrant parents from Prussia in Brookfield, Missouri in 1872 and studied architecture at the University of Illinois. After a stint teaching at Hyde Park High School, Levy established his architectural practice in 1904 with early work consisting of residential and mixed-use buildings.

A significant early commission came to Levy in 1906 when he was tasked with designing the Marks Nathan Jewish Orphan Home at 1548 S. Albany Ave. in North Lawndale. The Classical Revival style orphanage accommodated 300 children and included a synagogue, separate girls’ and boys’ wings, offices, a dining room, and employee quarters. In addition to designing the building, Levy supported the Marks Nathan Jewish Orphan Home for many years. Levy designed a number of synagogues in Chicago, and at least two survive. The oldest is from 1902 and was commissioned by the Ohave Sholom Miriampol congregation. Located at 733 S. Ashland Boulevard, Levy’s domed Classical Revival synagogue now is home to St. Basil Greek Orthodox Church. A decade later in 1912, Levy designed Ad Beth Hamedrash Hogodol with Sullivanesque ornament. It still stands at 5129 S. Indiana Avenue and now houses Unity Baptist Church.

Another significant work by Levy is his design for the Douglas Park Auditorium from 1910 at 3202 W. Ogden Ave. The Beaux Arts-style four-story building became a social and cultural center for the large Jewish community in North Lawndale.

In 1912, Levy designed his first theater, the Marshfield at 1650 W. Roosevelt Road on the Near West Side (demolished). It was the first of several that he would design for theater operators Louis and Meyer Marks who are discussed below. The web site Cinema Treasures identifies 15 theaters designed by Levy in Chicago, of this number only Apollo’s 2000 survives. In 1920, Levy formed a partnership with William J. Klein about whom little is known. The architectural firm of Levy & Klein was in business approximately from 1920 to 1939. Levy handled business and client side of the practice and Klein handled the engineering aspects of the firm. Levy’s specialty in theater design continued during his partnership with Klein. Important contributions to the firm’s theater practice were made by Edward Eichenbaum who joined in 1924 and became the lead designer of the firm’s ornate and palatial theaters of the 1920s. Examples of the firm’s movie palaces include the Diversey (1925), Marbro (1927), Regal (1928) and Granada (1930) theaters. Of this group, only the Diversey survives, now as a vertical mall and theater known as the Century.

In addition to theaters, Levy & Klein built many commercial and residential buildings

throughout Chicago, including the North Avenue Baths (1921) at 2039-45 W. North Ave. ( a contributing building in the Milwaukee Avenue District, a designated Chicago Landmark), and the Bryn Mawr Apartment Hotel (1928) at 5550 N. Kenmore Ave. (also a designated Chicago Landmark).

Movie Exhibitors Louis and Meyer Marks

Apollo’s 2000 was built as the Marshall Square Theatre by brothers Louis L. and Meyer S. Marks, as well as Julius Goodman. The Marks brothers were early pioneers of the movie theater business in Chicago who began establishing small, nickelodeon theaters in Chicago around 1910. These were almost certainly in existing buildings. However, by 1912 the Marks Brothers had grown large enough to build their first venue, the Marshfield Theater at 1650 W. Roosevelt Road on the Near West Side (demolished). With 296 seats, the Marshfield was typical of a first generation Chicago cinema. The brothers commissioned architect Alexander Levy to design the Marshfield and they would establish a long relationship with Levy as their business grew over the next two decades. In 1914, the brothers again hired Levy to design the Gold Theater (demolished) at 3411 W. Roosevelt Road in North Lawndale with more than double the seating capacity as the Marshfield. Along with the Marshall Square Theatre, now Apollo’s 2000, in 1917 the Marks Brothers built the Broadway Strand Theater (demolished) at 1641 W. Roosevelt Road on the Near West Side. Architect Levy designed the building with an arched terra-cotta façade and 1,500 seats, placing the Broadway Strand and the Marshall Square theaters in a new, second-generation of the theater design in Chicago.

In 1925, Louis and Meyer Marks established Marks Bros. Theatres, Inc., and began planning larger and more elaborate theater designs known as “movie palaces” similar to the Uptown and Chicago theaters, both designated Chicago Landmarks. To raise capital, the company began selling shares to the public. Advertisements for the stock offering credited the firm’s economic stability to its theatres which “offer popular priced entertainment to their patrons to whom theatre-going has become a real and important part of their daily lives.” The Marks’ expansion campaign resulted in the construction of two of Chicago’s largest and most-elaborated cinemas: the 3,500-seat Granada Theatre at 6427 N. Sheridan Road in Rogers Park completed in 1926; and the 4,000-seat Marbro Theater at 4110 W. Madison Street in Garfield Park, from 1927. Both came from architect Alexander Levy who had by this time had partnered with William J. Klein, though Edward C. Eichenbaum of their staff is credited with both designs in an elaborate Spanish Baroque style of architecture. Both buildings have been demolished. In 1928, the Marks brothers sold all of their theaters to Paramount Publix Corporation (later

Paramount Pictures) which hired the Chicago firm of Balaban and Katz to manage and operate the portfolio. Apollo’s 2000 appears to be the only Marks Brothers’ theater that survives.

Many thanks to the City of Chicago’s Historic Preservation publications for the information above.

Follow My Blog

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.